|

(Source texts of Landon's Literary Gazette publications are available as part of Dr Glen Dibert-Himes L.E.L. site.) Letitia Elizabeth Landon was one of the most widely read British poets of the early nineteenth century and one of the first women writers to achieve financial independence, consistent critical acclaim, and a huge public following from poetry. During the years of Landon's prodigious literary production (1820 to 1838), she published hundreds of poems in literary periodicals, produced seven individual books of poetry, contributed to a number of literary annuals, wrote most of the poetry for and edited the Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book for the years 1832 to 1839, authored three novels and an edition of poems and stories for children, edited (and some believe wrote) two other novels, published translations, wrote literary reviews and criticism, penned several plays, saw many of her poems set to music, and published numerous short stories. Her work was reviewed in most of the leading literary periodicals of the day and was widely distributed. Unfortunately her work has been obscured over the course of the last century and a half, and it has been so widely scattered that today's reader and scholar must struggle to find even a fraction of it. The small amount of her work that is generally available exists in the form of collections and anthologies that encompass only the written components of her art. These compilations of verbal texts only do not preserve either the nature of the substance of Landon's mature work, which typically consisted of both a visual text, such as an engraving, and the verbal text of an accompanying poem. Moreover, not only is this verbal material divorced from its visual components but, also it is often skewed chronologically and contextually. This volume represents a first stage in the process of retrieving an accurate and comprehensive collection of Landon's works; it brings together for the first time the poetry she published in the Literary Gazette. Many of the poems in this collection were very well-known in their day, yet most have not been republished elsewhere and are not included in any of the various "Complete Works" collections that appeared in England and America throughout the nineteenth century and, indeed, even in the twentieth century. This volume, then, offers our first modern look at the formative stages of Landon's artistic development and provides for us an overview of her efforts in the fugitive genre. This collection also provides a convenient representative sampling of the various poetic voices assumed by Landon and demonstrates the wide variety of poetic verse forms that she employed. The Literary Gazette

The Literary Gazette was established in 1817 by Henry Colburn, a publisher known for his aggressive marketing practices. It emerged on the scene at a time when British literary magazines were proliferating. At the turn of the century, a number of them, such as The Edinburgh Review, Blackwood's Magazine, and Quarterly Review, had gained wide acceptance and large readerships. Most of the periodicals, including these, were politically oriented and therefore evidence a particular bias in their editorial policies. Alvin Sullivan suggests that Colburn "shrewdly perceived" that a general audience existed that was not served by the politically charged periodicals and so he conceived a weekly that would cater mostly to this general readership (242). Such a forum would be useful to Colburn to promote his own publications through favorable book reviews, a practice called "puffing."  | | The formal title of the magazine was The Literary Gazette, and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, although a caption title, "London Literary Gazette," was sometimes used. | In July, 1817, Henry Colburn appointed one of his contributors, William Jerdan, as editor. Jerdan's tenure at the Gazette lasted until his retirement in 1850. Through the years he progressed from employee to shareholder to owner, wrote most of the articles, and was responsible for much of the magazine's character. Alvin Sullivan notes that Jerdan's main interest was literature, but because of a background in journalism, he had an eye for a scoop (242). Jerdan, like Colburn, was shrewdly attuned to the literary marketplace and did not hesitate to attempt to shape that market to his own advantage by promoting his literary friends, as well as Colburn's stable of writers. Throughout its life (1817 to 1863), the Gazette retained essentially the same format. The formal title of the magazine was The Literary Gazette, and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Sciences, although a caption title, "London Literary Gazette," was sometimes used. The typical issue consisted of approximately sixteen pages, type-set in three columns. Its lead article was always a book review, which usually occupied two or three pages, and which was followed by several other book reviews. The center part of the magazine was devoted to various feature sections, such as "Original Correspondence," a social column, a notice of theater productions, and "Original Poetry" sent to the magazine mostly by the public. The contributors to this section consisted of poets who were called "Correspondents," and some staff writers, who because of repeated appearances were recognized as featured writers. The last two pages of the periodical were devoted to advertisements for hire, usually promoting various book publications. In addition to these standard features, the Gazette offered articles on recent archaeological discoveries, inventions, and notices of art exhibitions. Illustrations appeared occasionally, but were relatively rare. Because of its wide circulation, focus on a general readership, and weekly format, the Gazette was considered one of the leading periodicals of its time. From the time of its inception The Literary Gazette had boasted a wide circulation, which as early as 1823 had reached 4,000-plus weekly issues. In 1830, near the middle of the Gazette's lifespan, an intense controversy erupted around the practice of puffing. The Athenaeum condemned the practice, declared its editorial independence, and drastically reduced its price. These changes pushed its circulation to over 14,000 weekly issues, a figure painfully superseding The Literary Gazette's circulation. Many periodicals, including the Gazette, changed in response to the Athenaeum's policy, leading to a virtual overhaul of editorial policies for British literary periodicals.

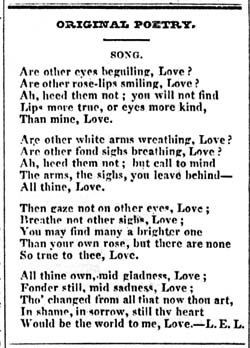

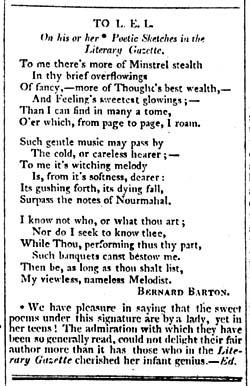

| | Landon became a featured writer in the Gazette's Original Poetry section | The "Original Poetry" section of The Literary Gazette, however. retained its popularity throughout the controversy, as it had since the magazine's inception. In the early years of the Gazette, "Original Poetry" occupied a relatively small amount of space. The 1820s, however, witnessed a marked change in the size and content of the feature, which was suddenly expanded because of the inclusion of a new and immediately popular poet who had emerged on the scene. Her first poetic attempts were included in the Gazette's "Original Poetry" section and after the publication of her first book of poetry, The Fate of Adelaide and Other Poems, which was favorably reviewed by the Gazette, her poetry began to be received enthusiastically by her readers. In fact, very quickly, her signature became immediately recognizable to the readers who loved to see her magical initials: "L.E.L." Landon and the Gazette The appearance of Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poetry and her enchanted signature in The Literary Gazette caused an immediate stir. Her contributions became almost weekly occupants in the "Original Poetry" section of the Gazette during 1822. Edward Bulwer-Lytton later recalled the sensation created by L.E.L.'s poetry among his fellow Cambridge undergraduates: There was always, in the reading room of the union, a rush every Saturday afternoon for the Literary Gazette; and an impatient anxiety to hasten at once to that corner of the sheet which contained the three magical letters 'L.E.L.' And all of us praised the verse, and all of us guessed at the author. We soon learned it was a female, and our admiration was doubled, and our conjectures tripled. Was she young? was she pretty? and--for there were some embryo fortune-hunters among us--was she rich? (546-7) Jerdan and Colburn must have been so happy they could hardly count. In 1818, when Jerdan first noticed her, L.E.L. was a young girl of sixteen who lived at Old Brompton, next door to the well-known editor. At a very young age Landon had displayed a considerable talent for story telling and had begun writing imaginative verse. Some of her earliest work, at the prompting of her mother, was given to Jerdan for his perusal and advice. Jerdan was much impressed with what he saw, though, as he put it, these early productions were "crude and inaccurate, as might be anticipated, in style" (175). He was impressed, however, with Landon's ideas which he found to be "original and powerful" (175). He not only offered the requested advice, but also saw that some of Landon's poetry found its way into The Literary Gazette. Landon's first Gazette offering, "Rome," appeared in the magazine in 1820. It was followed by several others in the weekly issues. Landon initially signed her verse "L." (the practice of signing poetry with initials was well established in the "Original Poetry" feature) and her poems appeared under the heading "By Correspondents." The best-known form of Landon's signature came after the Gazette favorably reviewed her first book of poetry, The Fate of Adelaide and Other Poems, in issue No. 237 (Sat. Aug. 4, 1821). The reviewer identified Landon by her full name, making her three initials identifiable, thereafter to the Gazette's readership. It was also after the review that Landon's inclusion under the heading "By Correspondents" ceased and she became, in practice and in fact, a featured writer. No promotional efforts, other than the review, are evident in the Gazette during the period of her artistic formation and signature change; it was the poetry that captivated the readers.  | | Captivated readers at times addressed poems to Landon's L.E.L. persona | During this period of emerging popularity, reader responses to the persona of L.E.L. and to her poetry appeared in the journal's pages and on a number of occasions these poetic responses were published beside her weekly offering(s). For example, the issue of February 15, 1823 contains the following editorial comment: It is something like self-praise to admit into our columns anything complimentary to what has appeared in them; but the many tributes we receive to the genius addressed in these lines will escape this censure, when we acknowledge them as due to a young and a female minstrel, and expressive of feelings very generally elicited by her beautiful productions. (107) The lines alluded to were called "To L.E.L." and began, "'Tis sweet, e'en to a wither'd heart,/ To hear the sounds that once were dear;/ When bliss and hope alike depart,/ Their echo soothes the lonely ear." L.E.L.'s effusions apparently found an appreciative older audience to complement her following among the young people at Cambridge and elsewhere. The "Original Poetry" section was a minor feature at best in The Literary Gazette when Landon's poetry began to appear. The feature was not included in every issue and when it did appear it contained a mixture of various compositions by a variety of writers. The "Original Poetry" feature was expanded during the period of L.E.L.'s involvement, often requiring five to six full columns, and was nearly exclusively her domain. Her poetry was such a recognized feature of the Gazette that in 1825 the editors began featuring her poetry in the year-end index. The entry for the "Original Poetry" section began to read "The poetry of L.E.L. can be found in . . . .". Previous to this, the section had given only the page numbers on which her poetry appeared. There is no question, then, that L.E.L.'s poetry had came to be highly regarded and that it was promoted by The Literary Gazette to their mutual benefit. One can deduce that, indeed, Landon was puffed by the Gazette. Leslie Marchand notes in his excellent study The Athenaeum: A Mirror of Victorian Culture that The Literary Gazette was very much in the thick of the controversy that emerged in the 1820s and 1830s concerning the common practice of booksellers (Henry Colburn in particular) who often maintained controlling interests in or owned literary periodicals and promoted with high praise the authors whose works they published. Marchand notes, however, that the case of L.E.L. was unusual: "Though she was as systematically puffed by her friends as any of the literary lights of her day, she struck a note which forestalled harsh criticism and vibrated a sympathetic chord in the breasts of the vast majority of her contemporaries and of all but the most daringly independent and unemotional of the critics" (146). Although she was occasionally negatively reviewed by the critics, L.E.L.'s work was for the most part favorably reviewed. She was able somehow to hold herself so successfully above the politics of publishing to the extent that throughout her career she maintained working relationships with many different and often competing editors and publishing firms. Jerdan offered her professionalism high praise when he remarked in his Autobiography that L.E.L was for many years "an effective colleague" on the Literary Gazette (173). Letitia Elizabeth Landon possessed the remarkable ability to assume a number of different literary personalities over the course of her very eminent career. She developed and customized her poetry to suit her publishing venues. For The Literary Gazette and other literary periodicals, she was "L.E.L." who enthralled her readers with a variety of poetic styles. Here we find examples of L.E.L.'s use of subgenres like the Romantic fragment, short poems which she called "songs," narrative poems, a few sonnets, epigrams, a form she called "stanzas," various kinds of "poetic illustrations," and dramatic sketches in verse. The literary periodicals, especially the Gazette, became for L.E.L. a means of presenting, and perhaps "testing," various forms of poetic expressions and voices. In her books of poetry, she was the "Improvisatrice"--the poet who extemporized variations upon imaginative tales which were often set in the glorious past or in distant and exotic lands. As the editor of the British literary annual Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book and as a frequent contributor to many others annuals, Landon was the poetic illustrator for visual representation. She stated that the work she did in the annuals was some of her best, but she found her earliest voice through the pages of The Literary Gazette. This fascinating collection not only shows the variety of her poetic expression, but also provides insight into her development as a artist. L.E.L.'s poetry has much to offer today's reader; her song is melodic, her imagery rich, and her poetic narratives are some of the finest in the language. She has been credited with developing a distinct school of poetry that was influential in both England and America. L.E.L.'s poetry represents a unique and finely tuned form of British Romanticism--an applied Romanticism--yet in many ways marks the transition in British literature to Victorian artistic sensibilities. Unfortunately, readers today are much removed from the actual context that in her own time surrounded her poetic expression. A look at some of the contemporary discussion of L.E.L.'s poetic genius will provide access to her poetry and enable us to enjoy the richness of her writing by giving us some understanding of just what the contemporary reader found so appealing about it. Landon and the Initial School As early as 1829, L.E.L. was formally recognized by critics as the founder of a distinct school of poetry. In the February 14, 1829 issue of The Literary Gazette appeared a review of The Token, which was an American literary annual that was published in both England and the United States. The reviewer points out that the poetry contained in this annual is strongly influenced by L.E.L. The review reveals something of the nature of the school of Landon's poetry as it was conceived by her contemporaries: Their style is modelled on the school of which she is the founder: the same vein of metaphysical sentiment; the same wish to give inanimate nature our own feelings, making a sympathy between them, sometimes fanciful, but oftener touching; the same desire to exalt the humanity of love by the refinement of sorrow; the short sketches in blank verse. (100) The specific reference here is to L.E.L.'s poetry, which typically consists of a poetic response to a visual stimulus that is printed beside the poetry (in the Literary Gazette, illustrations were not actually included with L.E.L.'s poems; however, reference is often made to the visual source to which she is responding). The reviewer describes the symbiotic relationship that is created between the visual stimulus, often a work of art such as a painting or an engraving, and the poet's imagination. Energized by "genius," a synthesis occurs within the poet that produces a metaphysical overlay that is then projected via the poetry to the audience. Sarah Sheppard, a contemporary and friend of Landon's, called it a "rainbow hue" that extends from the poem to the reader. A second stage of symbiosis is then created between the reader and the persona behind the poetry. This is not, however, an autobiographical presence. Landon often lamented the fact that critics, whom she believed did not really understand her poetry, too often associated her personality with the narrative or appreciated personae of the poetry. Instead of autobiographical sketches, what is generated by the symbiotic relationships is a sympathy between the art and the audience, which results in an emotional and intellectual response. Perhaps a better way to describe the relationship is in terms of a sympathetic discourse between the art and the audience with the poet's creative imagination serving as the conduit. Love, sorrow, and death are common themes in Landon's poetry and, as the reviewer above points out, the motive behind the treatment of these themes is "the desire to exalt the humanity of love by the refinement of sorrow." The attitude of the poetic persona is often melancholic. By bringing the reader into a mental and emotional discourse within a melancholic atmosphere, a refinement occurs that exalts the "humanity of love." The poetic synthesis of metaphysical sentiment, accomplished by lending the inanimate our own feelings, creates exaltation and, by implication, understanding. We can bring this complex poetic aesthetic into better focus by turning to Sarah Sheppard's 1841 detailed analysis of Landon's art, Characteristics and Genius of the Writings of L.E.L.. Sheppard's intricate analysis offers a much more searching discussion of the specific characteristics, outlined in brief in the review above, of L.E.L.'s art. Sheppard's stated purpose for her book is to answer hostile critics by demonstrating L.E.L.'s genius (it should be noted that Sheppard was already preparing this critical analysis before L.E.L.'s death). The tone of Sheppard's criticism is defensive because L.E.L.'s work was being challenged by changing artistic philosophies--Sheppard calls them "pseudo-utilitarian" (14). Looming behind Sheppard's defense is an emerging conflict between two very different theories of art. One theory, characteristic of Romanticism, stresses the artist's capacity to recast observation or reflection through the workings of the imagination combined with fancy into a finely tuned and amplified imaging. This is a metaphysical process that produces sublime effects. The competing theory, characteristic of some Victorian art, rejects such a notion as silly and sentimental and favors a rational, analytical artist who practices accurate observation and faithful representation, usually designed to provide practical instruction. The specific complaints of the pseudo-utilitarians concerning L.E.L.'s "school" are recorded disparagingly in the Literary Gazette's October 24, 1835 review of L.E.L.'s simultaneously published book of poetry, The Vow of the Peacock and other poems: Pseudo-Utilitarians tell us that the love of poetry is over; and that, under their auspices, the human kind have become a mere shrewd, calculating, sordid, work-o'-day race. That to toil, and to spin, to draw water, and cleave wood, to gather and amass, to drudge and hoard, and never to enjoy, is the wisdom, the only wisdom, of life. We are ready to believe their doctrines when we shall be convinced that the love of gracefulness and beauty, the fine moral perception, the sense which gives a tear to sorrow, the noble enthusiasm awakened by illustrious deeds--when natural feeling, sympathy, generosity, and heroic aspiring, have all departed from among the children of men. And not till then. In the mean time the appearance of the Vow of the Peacock will put the theory to the test. If its charms are generally despised, we shall hasten to enlist in the ranks of Utilitarianism, and try to forget that ever Imagination could impart a delight to the soul. If it fail to excite the same emotions and the same admiration, which have in all bygone ages rewarded the magic of song, we must become converts to the hypothesis that the world is changed, and that stocks and stones, in the automaton shape of human beings, have usurped the place hitherto occupied by creatures endowed with apprehension and passions. (673) Sheppard picks up the argument and advances it by stating that the trend is to impose upon art utilitarian properties that fall into rational and scientific forms of discourse--a sort of philosophical objectification. She insists that to do so is to lose completely the poetic genius of L.E.L, and specifically, to lose sight of the fact that her genius was "poetic" and metaphysical in nature, that it threw a "rainbow hue" over the subject matter, and that it was, indeed, a very different kind of discourse. She insists that those who criticize L.E.L.'s art are blinded by the "new" pseudo-utilitarian theory of art so that L.E.L.'s synthetic creations are incomprehensible and therefore meaningless to them. "Poetical Genius" is the energizing agent that Sheppard associates with L.E.L. She writes, "In the universe of mind and the world of poetry, brilliant effects require for their productions the spontaneous impulses of genius, their first cause, together with the combined and often recondite workings of all the agencies which constitute the intellectual being" (14-15). Sheppard stresses the creative aspect of Landon's work. In her view, L.E.L. goes beyond merely amplifying what already exists in nature, producing a wholly original act of creation. She argues that it is the poet's especial province to create purely intellectual sources of enjoyment from the synthesis of sensual input in the poetic imagination (17). Sheppard discusses L.E.L.'s appreciation of art to demonstrate her creative process: How did pictures ever seem to speak to her soul! how would she seize on some interesting characteristic in the painting or engraving before her, and inspire it with new life, till that pictured scene spread before you in bright association with some touching history or spirit-stirring poem! L.E.L.'s appreciation of painting, like that of music, was intellectual rather than mechanical,--belonging to the combinations rather than to the details; she loved the poetical effects and suggestive influences of the Arts, although caring not for their mere technicalities. (18) What L.E.L.'s readers appreciated in her creations was that "new life" that she brought to her subject. Her imaginative re-castings produced intellectual pleasure for her audience. The wonderful characteristic of L.E.L.'s writings, which her readers recognized, was the author's special creative capacity to bring new meanings to her audience. Sheppard notes, "Very often her remarks, as she read or recited any passage, would throw a new light upon what previously might have been to her hearers a hidden meaning; or enhance the value of what had been even frequently read and admired" (18). L.E.L.'s imagination was bold and free and her expression unrestrained. Sheppard records an incident in which Landon wrote to a young author, "Criticism never yet benefited a really original mind; such a mind macadamizes its own road" (19). It is no wonder that L.E.L.'s free spirit raised the hackles of the sober-minded Utilitarians. Sheppard next discusses some of what she calls the "Peculiarities of L.E.L.'s Works." Again, she is responding to Utilitarian criticisms of Landon. She writes, "The first of these objections applies to the manner or rather style of her poetry. 'It is too flowery and frivolous, consisting in a heap of words prettily strung together with very little meaning, and entitled to no higher rank than is implied in the sarcastic phrase of "Young Ladies' Verses"'" (20). Sheppard responds to this censure, "To some minds the rainbow may seem no more than bright colours; they think not of its causes, its purpose, nor why its magnificent archway bridges the earth and sky with a glory caught from the fountain of life and light" (20). Sheppard makes a point--if one is not receptive to the effects of L.E.L.'s writing, they will be lost. Sheppard further distills her argument by pointing out the difference between Philosophy and Poetry: "For while Philosophy piles its massive bridges of reasoning across the deep streams of thought, Poetry gracefully throws over the them its suspended chain-work, which combines equal safety with greater elegance" (21). She argues that poetry and philosophy might endeavor to reach toward the same objectives, but employ different means: It does not follow, therefore, [referring to her previous distinctions between philosophy and poetry] that truth and right reason must be absent when the manner of their exposition differs from that employed in the abstract sciences, to which truth is supposed essentially to belong. A geometrical diagram itself may be equally correct in all its parts, though drawn in golden lines on tablets of silver as if sketched in the roughest manner with the rudest materials . . . So truths are not less true when decorated with the graces of poetry than when contemplated in the abstract . . . . " (21-22) Indeed, truth may be beauty and beauty truth. In fact, these "Young Ladies' Verses" may communicate truths incomprehensible to the Utilitarian sage. The second objection countered Sheppard sets out to counter concerns the subject matter of L.E.L.'s poetry--love. Sheppard readily admits that love is a frequent theme in L.E.L.'s work. She answers the "philosopher's" objections with philosophy, pointing out that philosophers admit that love is an essential component of human nature. She argues that since L.E.L. is a poet who explores aspects of the human condition, it is entirely consistent that she dwell on such an integral aspect of human concern. She quotes Landon on the subject, "Even into philosophy is carried the deeper truth of the heart" (23). Sheppard then cites several testimonies "from high authorities in the intellectual empire" in support of the notion that, indeed, love is an important concern for everyone (24). She points out that "Philosophy will tell us that love is the excitement of one class of our susceptibilities,--one order of our moral emotions"; therefore, why shouldn't L.E.L. use love as a subject matter (22)? In other words the "philosopher's" criticisms of Landon's subject matter are self-contradictory. Sheppard then takes her argument a bit deeper, and it is especially relevant to the statement from the review given above concerning Landon's concern with the refinement of the "humanity of love." She writes: It is an affection [love] whose right use is not more productive of virtue and happiness than its neglect and abuse tend to vice and misery. By the refining and humanizing--by the brightening and soothing--by the generous and expanding influences which affection diffuses over the world, it holds its place among the component elements of the happiness and good of the social system. 'It is affection,' observes the philosopher already quoted [Dr. T. Brown], 'which in some of its forms, if I ma

© 1998 Glenn T. Himes / Sheffield Hallam University

|